Message

Persia and the Allure Of The Santour:

Pouri Anavian

It is customary for Persians to take gifts when paying a visit. When Persians visited Nara,

the ancient capital of Japan, 1,300 years ago, they bore porcelain, bronze, silk and musical

instruments, offering them in tribute to the dignitaries.

Persia was an advanced empire, spread out across the Eurasian continent.

Persian merchants sowed seeds of culture while traveling east along the Silk Road trade

routes. They carried their innovations in fine art, merchandized them and set trends,

inspiring and exposing Japan to a new world.

After all the time that has passed, Japan and Iran's relationship today depends

primarily on oil. The cultural ties have been cut off for over a thousand years.

Seeking to revive the glorious past, Pouri Anavian, musician and lecturer at Osaka

College of Music, introduces the exotic sound of the santour, a traditional Persian musical

instrument recognized as a precursor of the piano.

She introduces her students to the wonder of the santour, opening their ears, hearts

and minds to an ancient but fresh sound. When she began teaching at the university, a few

students (unfamiliar with the music) took her class just for fun, as a supplemental course

in 'ethnic music'. However, the sublime spirit of Persian music captured the imagination of

the students.

Persian classical music utilizes a large variety of diatonic scales such as quartertones

or semi-tones, a dizzying variety of tones, which are non-existent in the European canon.

The sphere of musical possibility offers musicians a path to subtler expression and vast

innovatation.

Though in general student enrollment at universities is decreasing in Japan, her

santour class continues to expand and gain popularity. Through the Persian melodies which have survived and been passed along for thousands of years, Pouri wishes to reignite a flame of friendship between the ancient cultures.

Profile

Pouri Anavian: Art Maven, Santourist, Author Of Persian-Japanese Conversation Book

Musical Accomplishments

Pouri Anavian performed her first santour concert at the age of five

in Tehran. Majoring in piano (under the tutelage of Professor Javaad

Marufi) and musicology, she graduated from the Music Conservatoire and

then attended Tehran University. Upon moving to Japan in 1972, at the

age of twenty-six, she studied piano with Professor Okumura, formerly

of the prestigious Julliard School of Music in New York.

It was her first instrument, the santour, a precursor of the piano,

which jump-started her professional career. The Japanese National

Broadcasting Corporation (NHK), intrigued by the unique sound of

the seventy-two-stringed instrument, contracted with her to perform

the soundtrack of "Mibu No Koi Uta". She honed her skills for this

weekly television drama. A saga about the samurai of the Edo Era, the

production enjoyed a six-month broadcast.

Since then, she has performed in cultural centers, concert

halls and even played several times for members of the Japanese

Imperial Family. Her activities celebrating traditional Persian music and

culture have been frequently reviewed with acclaim in newspapers and

magazines in Japan. By popular demand, she is presenting more concerts

and cultural programs than ever.

At present, Pouri Anavian is a lecturer at Osaka College of Music, where she has

taught the santour to over five hundred students in the past twenty-nine years.

Cultural Ambassador

In 1978 Pouri Anavian published the first Persian conversation book

for the Japanese public.

She was one of the founders of the Persian Shawl Pavilion of the

Asia Museum, in Tottori Prefecture in 1993 and also provided one of the

world's most impressive and important Persian brocade collections for

it. The 2000-piece lot, including shawls, robes and murals, was mostly

commissioned by the Persian Royal family and painstakingly and lovingly

culled by her father, a legendary art connoisseur.

Playing an important role in the establishment of The Hamamatsu

Museum of Musical Instruments in 1995, she researched, advised about,

purchased and supplied a collection of traditional musical instruments of

the Silk Road from Greater Persia (including Turkey and Central Asia) for

the center.

Ever striving to revive her cultural heritage, Pouri annually invites to

Japan accomplished artists – classical and folk music ensembles, dancers,

poets, painters, calligraphers and artisans – to stage programs and

shows.

In 2002, she traveled to Tehran with six of her female Japanese santour students. Dressed in veils and kimonos, as a tribute to both

cultures, Pouri and her troupe presented a critically-praised concert in

Honar Saraye Niyaavaraan in Tehran, the first-ever concert of its kind.

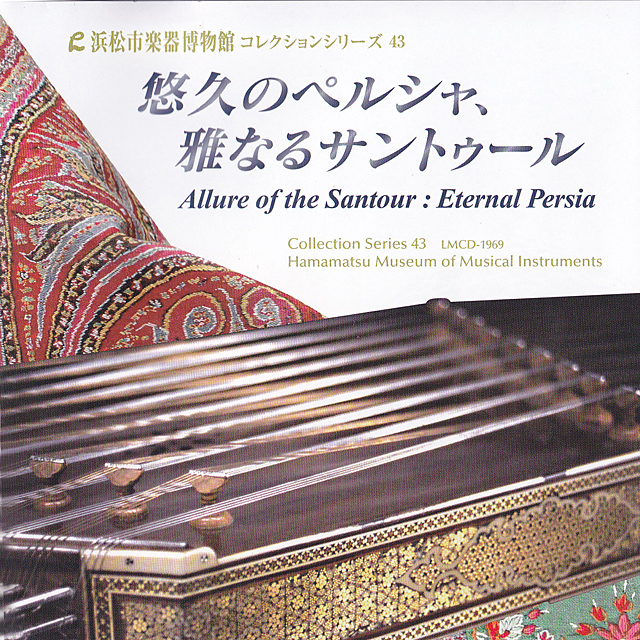

Discography

Newly-published Discography (Spring, 2013)

Allure of the Santour:Eternal Persia

Produced by Hamamatsu Museum of Musical Instruments

Telephone: 053-451-1128

http://www.gakkihaku.jp

Santour

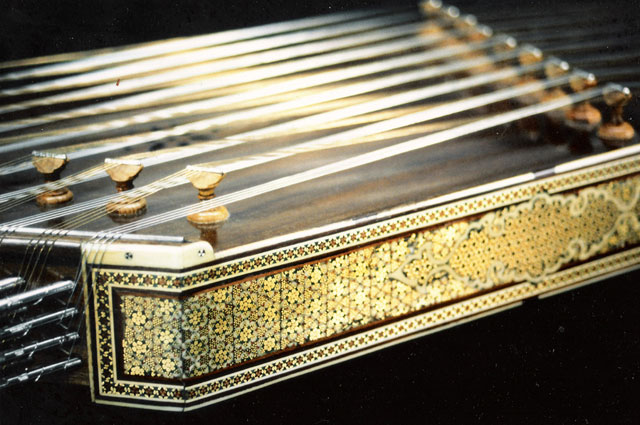

Santour: The Dulcimer of Persia,

Seventy-Two Stringed Santour Evokes Paradise

A precursor of the piano, the santour has a trapezoid shape, seventy-

two strings and is performed on with specially shaped, lightweight, mallets

(mezrab) held between the index and middle fingers. Played around the

world, it is sometimes differently designed and known by other names. In

Persia, walnut wood has traditionally been most suitable for its quality of

sound.

There are eighteen slightly spaced groups of four uni-toned strings,

resting on kharaks ("little wooden donkeys", donkeys because the strings

rest on their backs) stretched horizontally across the instrument.

The santour has three octaves, each one nine tones, which means it

has twenty-seven tones in all. The strings supported by the nine kharaks

on the right side are brass, while those supported by the nine kharaks

on the left side are steel. In other words, the four-stringed groups are

alternately brass or steel.

A standard felt-tipped mallet weighs 1.5 grams. Incidentally, felt has

been used only in the last one hundred years. For a variety of sonic

effects, however, Pouri employs two kinds of mallets, achieving a softer

modern sound with the felt and a more resonant ancient sound without. On

occasion, she will even change mallets in the same composition.

Pouri also uses the santour bass, a newer slightly bigger version of the

santour, but one octave lower. The santour bass has been used for only

the last 30 to 40 years in orchestras in Iran. She uses it for duets and

sometimes when she performs solo. It requires a different technique of

hammering.

Considerable time is required for tuning the santour. Each melody requires

a different scale from the twelve modes of Persian classical music.

European classical music is simplified in two modes, major and minor,

while Persian classical music consists of twelve modes (dasgah). One of

them is called mahur (major), while another is esphahan (minor). There

are ten more modes, with ten modes within each of those. In fact, it is

endless – with modes within modes within modes. Pouri Anavian often

takes several santours for a single concert in order to be able to play in these extensive modes.

The prototype of this trapezoid-shaped instrument was first chronicled

three thousand years ago during the Assyrian Period. The intestines of

sheep were used for the strings, probably resulting in a cruder sound.

In the thirteenth century, when trade flourished along the Silk Road, they

used - what else - silk for the strings.

As it traveled west to Europe, the instrument eventually evolved - as

craftsmen fashioned legs, handles, keys and a cover, - into a piano.

In Japan, during the Edo Period (300 years ago), it was introduced as the

yaukin, the Chinese characters translating to 'night' (ya) – 'rain' (u) –'koto'

(kin). However, the instrument was lost and forgotten in Japan until 1983

when Pouri performed the soundtrack of "Mibu No Koi Uta", a weekly

television saga about the samurai of the Edo Era.

Pouri Anavian, one of the very few professional santourists in Japan, hopes

this instrument will help to deepen the cultural ties between Japan and

Iran.

Persian music

Largely inspired by the magnificence of nature, Persian music is said to be five

thousand years old, The verdant landscape and chirping lovebirds fluttering in meadows full of flowers are quintessential emblems of both the poetry and

music of an oasis. As the winged creatures twittered, besotted composers

recorded these rhythms in their heads and hearts. In fact, one of the loveliest

recurring themes in Persian music and poetry is the birds singing to flowers,

with the flowers emitting their heady fragrance in reply. So was the birth of

Persian music.

Publication

Persian Phrasebook: Great Companion For Japanese Traveling In Iran

In the good old days (1978) when Iran was a tourist paradise, I published the first Persian

phrase and vocabulary book in Japanese. Since hardly any Japanese nor Persians could

communicate in English, I thought a simple phrasebook could be the first step for them to

speak together.

With this book, you'll be able to haggle in the bazaar and chat with your hairdresser

– basically, talk with the locals.

At home my father, Rahim Anavian, a respected and internationally recognized art

dealer and historian, regularly entertained Japanese scholars specializing in West Asia. So,

early on, I admired and was intrigued by the mystery of the Far East, as well as its rapid

technological development.

When I moved here in 1972 there was no Japanese conversation book in Persian.

There were many academic books but they were not practical to carry around or enhance

casual conversation.

The students I met at Osaka University School Of Foreign Studies, though they

tried, spoke stiffly because most textbooks focus on strengthening students' reading, not

chatting.

Everyday Persian conversation is different from what students read in books. I

thought, if no one's going to write one, then I'll do it myself.

I found myself a Japanese professor from the university to help me write the book. It took

two years with numerous obstacles to complete the project. Naturally, with the customs and

lifestyles being different, there are expressions that can't be translated into Japanese.

The biggest challenge was getting the pronunciation clear. I used my background in

music and two of the three Japanese alphabets, hiragana for high tones and katakana for

low tones, to place accents on the right syllables.

Once the book was essentially finished, I had the professor and a friend pore over it

several times so it would be as accurate as possible.

Tokyo University archaeology professor Egami Namio, once a frequent traveler to

Iran, proclaimed it "a meticulous piece of work."

So, this is your indispensable friend and guide for your journey to Iran.